Abstract

Serotonin 1A (5-HT1A) binding potential (BP) as assessed by positron emission tomography (PET) is higher in major depressive disorder (MDD) in association with the higher expressing GG genotype of the 5-HT1A C-1019G polymorphism. We hypothesize that higher 5-HT1A BP and the GG genotype predict remission failure on antidepressant treatment. We determined 5-HT1A BP by PET and 5-HT1A C-1019G genotype in 43 controls and 22 medication-free MDD subjects. MDD was treated naturalistically and remission was defined as >50% reduction and a score of ⩽10 on the 24 item Hamilton Scale 1 year after initiation of treatment after scanning. Despite equivalent treatment, nonremitters have higher pretreatment cortical BP and the GG genotype is over-represented compared with remitters. Higher 5-HT1A BP, perhaps due to greater gene expression, may predict antidepressant medication nonremission. The findings should be tested in a controlled prospective treatment study.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

An association between the functional C-1019G promoter polymorphism of the 5-HT1A gene and major depressive disorder (MDD) has been reported; MDD subjects are more likely to be homozygous for the GG genotype (Lemonde et al, 2003). The authors show that the C(-1019) allele is part of a 26 bp imperfect palindrome that binds the nuclear deformed epidermal autoregulatory factor (NUDR) transcriptional repressor, resulting in increased expression of the 5-HT1A protein in the raphe nuclei (RN). Antidepressant naïve (AN) MDD subjects in a major depressive episode (MDE) exhibit higher 5-HT1A binding potential (BP) in several brain regions when compared with controls as assessed in vivo using the positron emission tomography (PET) radioligand, [11C]WAY-100635 (Parsey et al, in press). Further, GG depressed subjects are more likely to have higher 5-HT1A BP (Parsey et al, in press). A poorer response to antidepressant treatment appears to be associated with the higher expressing GG genotype (Albert, 2004; Lemonde et al, 2004; Serretti et al, 2004).

We investigated the role of the 5-HT1A receptor and C-1019G promoter polymorphism in predicting antidepressant treatment outcome by analyzing 1 year follow-up data from our previous PET study (Parsey et al, in press) using [11C]WAY-100635 in 22 drug-free subjects with MDD who met criteria for a MDE and 43 healthy volunteers (controls). We hypothesized that MDD subjects exposed to community-based treatment and not in remission after 1 year would have higher 5-HT1A BP and be more likely to have the higher expressing GG genotype compared with remitters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

In total, 22 subjects who met DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria for MDD and MDE and 43 controls were included in this study. Inclusion criteria was assessed through history, chart review, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV (SCID I) (First et al, 1995), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (Hamilton, 1960), review of systems, physical examination, routine blood tests, pregnancy test, urine toxicology, and EKG and are described elsewhere (Parsey et al, in press). Lifetime history of aggression was measured by the Brown Goodwin Aggression History Scale (Brown et al, 1979). Outcome assessments of 1 year included a clinical interview and the 24-item HAM-D. In total, 28 subjects were scanned at baseline and their data presented in a previous publication (Parsey et al, in press). Six of these depressed subjects did not receive 1-year post-treatment ratings; five were lost to follow-up and one missed the 1-year follow-up. Remission was defined as at least a 50% decrease from HAM-D 24 baseline score and a score of ⩽10 at the 1-year assessment (Bschor et al, 2002; Bschor et al, 2003; Keller, 2004; Lin et al, 1998; Paykel et al, 1995; Roose and Suthers, 1998; Smith et al, 2002). All subjects were treated with antidepressant medications during the year. In all, 14 of 22 were on medications at 1 year. A computerized version of the Antidepressant Treatment History Form (ATHF) was used to assess the adequacy of treatment during the year following the baseline PET scan (Oquendo et al, 2003; Sackeim et al, 1990). All subjects were medication-free for at least 2 weeks. The Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University New York Presbyterian Hospital and the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the protocol. Subjects gave written informed consent after an explanation of the study and were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Radiochemistry and Input Function Measurement

[11C]WAY-100635 synthesis, measurement of the arterial input function and metabolites, and determination of the plasma free fraction (f1) are described elsewhere (Parsey et al, 2005).

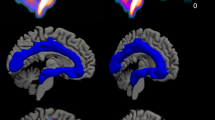

Image Analysis

Acquisitions of MRI and PET data and image analysis were performed as described elsewhere (Parsey et al, 2005). Briefly, dynamic PET images were acquired over 110 min following a 10 min transmission scan and were coregistered to the MRI. Irregular regions of interest (ROIs) traced on MRIs were transferred to the coregistered PET images. Cerebellar white matter was used as the reference region (Parsey et al, 2005) and the volume of distribution (V2) did not differ among the remitters, nonremitters, and control group (F=0.887; df=2, 62; p=0.417). Regional distribution volumes of [11C]WAY-100635 were derived using an arterial input function as described previously (Parsey et al, 2005). Cerebellar V2 from a one tissue (1T) compartment model was used as a constraint for the K1/k2 ratio in the two tissue (2T) kinetic modeling of the ROI. BP was calculated as (VT−V2)/f1, where f1 is the free fraction in plasma.

Statistics

Statistical analyses performed included Student's t-test, one way analysis of variance, and linear mixed models analysis with subject as the random effect. Model fitting was computed using both SPSS 11 for Mac OSX (www.spss.com) and R (www.R-project.org). When multiple regions were considered in a single analysis, region was included as a fixed effect, and the analysis was performed on the natural log of BP, in order to account for heterogeneity of variances across regions. Significance was defined as p<0.05 and p-values are reported without multiple comparison adjustment. All tests were two-sided.

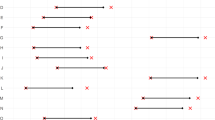

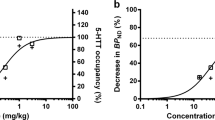

RESULTS

Baseline HAM-D scores were comparable in nonremitters and remitters (Table 1, p=0.783). By definition, at the 1-year time-point, nonremitters had significantly higher scores on the HAM-D (23.2±8.8) than remitters (4.3±3.5, p<0.001). Nonremitters, remitters and controls did not differ in the injected mass of [11C]WAY-100635 (controls=6.9±4.5 nmol; nonremitters=6.1±2.5 nmol; remitters=5.0±2.4 nmol) or injected dose of [11C]WAY-100635 (controls=8.4±3.6 mCi, nonremitters=10.4±4.4 mCi; remitters=8.3±3.4 mCi). There is a difference in f1 among the three groups (F=7.87; df=2, 62; p=0.0009; controls=8.1±2.6; nonremitters=5.7±2.9; remitters=8.5±2.3, Figure 1). The non-remitter group had higher 5-HT1A BP ((VT−V2)/f1) compared with the remitter group across all brain regions (F=5.29; df=1, 61; p=0.025; see Figure 2). There was also a significant interaction of responder status with region (F=3.87; df=12, 744; p<0.001), and the difference was significant (p<0.05, uncorrected for multiple comparisons) for each region except amygdala (AMY, p=0.054) and raphe nucleus (RN, p=0.517), although none of the region-specific comparisons would survive a Bonferroni correction.

Nonremitters have increased BP across regions compared to remitters and controls (RN=raphe nuclei, VPFC=ventral prefrontal cortex, MPFC=medial PFC, DLPFC=dorsolateral PFC, ACN=anterior cingulate, CIN=cingulate body, AMY=amygdala, HIP=hippocampus, PHG=parahippocampal gyrus, INS=insula, TEM=temporal cortex, PAR=parietal cortex, OCC=occipital cortex).

The nonremitter and remitter groups did not differ in the adequacy of treatment during the year between the scan and the 1-year follow-up assessments as measured by the ATHF score (nonremitters=2.6±1.7; remitters=2.9±1.3, p=0.691). They also did not differ in any demographic variables measured (Table 1). We have previously reported higher BP in AN medication-free MDD subjects compared to subjects who had previous exposure to antidepressants (Parsey et al, in press) and so this effect was included in the model. We found no interaction between prior medication status and remission status (F=0.158; df=1, 62; p=0.693). Including age, sex, and lifetime aggression (Parsey et al, 2002) in the model did not affect the results; remitter status remained significant (F=4.33; df=1, 57; p=0.042).

We report that depressed subjects and controls with at least one G allele of the C-1019G polymorphism have higher BP in the raphe (Parsey et al, in press). We found an association in genotype distribution (χ2=10.7, df=2, p=0.005) but not in allele frequency (χ2=3.58, df=1, p=0.058) between the control group and nonremitters (Table 1). Nonremitters have 3.5-fold greater incidence of GG genotype than remitters.

DISCUSSION

Nonremission of major depression after 1 year of community-based treatment is associated with higher pretreatment 5-HT1A BP and the higher expressing GG genotype. These data suggest the following 5-HT1A model for MDD: the GG polymorphism is associated with greater 5-HT1A gene expression in the RN and hence more 5-HT1A binding. As the 5-HT1A receptors are presynaptic, more 5-HT1A raphe autoreceptors would result in less serotonin neuron firing and decreased terminal field 5-HT release. This could be followed by a homeostatic upregulation of postsynaptic terminal field 5-HT1A receptors. The GG genotype is also associated with resistance to a variety of antidepressant treatments (Albert, 2004; Lemonde et al, 2004). Our data are consistent with this hypothesis; treatment resistant MDD have higher 5-HT1A receptors. Although we observe apparently higher mean autoreceptor 5-HT1A in GG nonremitter subjects in the raphe, the effect is not statistically significant perhaps due to power limitations due to sample size and a lower signal to noise ratio in this small ROI. If it can be confirmed that there are more 5-HT1A autoreceptors in nonremitters, then these subjects may be resistant to treatment because the genetic variant may interfere with SSRI-mediated desensitization or downregulation of the presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors (Paul Albert, personal communication and (Blier et al, 1987)). A striking observation is that the remitters have 5-HT1A binding comparable to the controls. Perhaps they respond to medication, particularly SSRIs because their serotonin system is less compromised biologically and genetically.

One nonremitter had an unusually large measurement for f1 relative to the others (Figure 1). Repeating the analysis with this subject removed did not change the conclusions, as the effect of remitter status was still significant (F=7.79; df=1, 60; p=0.007).

We have previously shown that MDD subjects who were never medicated had higher 5-HT1A BP than previously medicated and control subjects. This finding is unrelated to the current finding; there is no relationship between medication status and treatment response. The findings of increased 5-HT1A BP in never medicated MDD subjects is at odds with some of the previously published in vivo and in vitro data and have been discussed extensively elsewhere (Parsey et al, in press). For in vivo studies, differences in image acquisition, analysis, previous exposure to antidepressant medications, and patient populations may account for these discrepancies. For in vitro studies, in all cases, the controls are compared to suicide victims who have Axis I diagnoses, most commonly MDD. None of the published studies, to our knowledge, has compared controls to MDD subjects without suicide. None of these studies has examined the ability of 5-HT1A receptors to predict treatment response.

This study is not a prospective study with a controlled antidepressant treatment; rather it was an exploratory analysis of open, un-blinded, community-based treatment. Future studies should compare prediction of serotonin-selective and norepinephrine-selective antidepressants to see if outcome prediction is comparable for these different classes of medication. The current sample is relatively small and the results are preliminary.

Conclusions

This preliminary naturalistic study indicates that higher 5-HT1A binding is associated with a poorer response to antidepressant treatment and that MDD subjects who failed to respond to antidepressant treatment were more like to posses the GG genotype. Future prospective studies with a standardized treatment in a larger cohort are needed to determine the utility of 5-HT1A binding or genotype in treatment planning.

References

Albert PR (2004). A functional promoter polymorphism of the 5-HT1A receptor gene: association with depression and completed suicide. Biol Psychiatry 55: 46S.

APA (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Blier P, de Montigny C, Chaput Y (1987). Modifications of the serotonin system by antidepressant treatments: implications for the therapeutic response in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 7: 24S–35S.

Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF (1979). Aggression in human correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1: 131–139.

Bschor T, Adli M, Baethge C, Eichmann U, Ising M, Uhr M et al (2002). Lithium augmentation increases the ACTH and cortisol response in the combined DEX/CRH test in unipolar major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 27: 470–478.

Bschor T, Baethge C, Adli M, Eichmann U, Ising M, Uhr M et al (2003). Association between response to lithium augmentation and the combined DEX/CRH test in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 37: 135–143.

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J (1995). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York.

Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23: 56–62.

Keller MB (2004). Remission versus response: the new gold standard of antidepressant care. J Clin Psychiatry 65 (Suppl 4): 53–59.

Lemonde S, Du L, Bakish D, Hrdina P, Albert PR (2004). Association of the C(1019)G 5-HT1A functional promoter polymorphism with antidepressant response. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 7: 501–506.

Lemonde S, Turecki G, Bakish D, Du L, Hrdina PD, Bown CD et al (2003). Impaired repression at a 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor gene polymorphism associated with major depression and suicide. J Neurosci 23: 8788–8799.

Lin EH, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, Russo JE, Simon GE, Bush TM et al (1998). Relapse of depression in primary care. Rate and clinical predictors. Arch Fam Med 7: 443–449.

Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E, Kartachov A, Khait V, Campbell CE, Richards M et al (2003). A computer algorithm for calculating the adequacy of antidepressant treatment in unipolar and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 825–833.

Parsey RV, Arango V, Olvet DM, Oquendo M, Van Heertum R, Mann JJ (2005). Regional heterogeneity of 5-HT1A receptors in human cerebellum as assessed by positron emission tomograph. J Cerebr Blood F Met 25: 785–793.

Parsey RV, Oquendo M, Ogden RT, Olvet DM, Simpson N, Huang Y et al (in press). Altered serotonin 1A binding in major depression: A [carbonyl-C-11]WAY100635 positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry, 8 September 2005 [E-pub ahead of print].

Parsey RV, Oquendo MA, Simpson NR, Ogden RT, Van Heertum R, Arango V et al (2002). Effects of sex, age, and aggressive traits in man on brain serotonin 5-HT(1A) receptor binding potential measured by PET using [C-11]WAY-100635. Brain Res 954: 173–182.

Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Kerr J, Barocka A (1995). Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med 25: 1171–1180.

Roose SP, Suthers KM (1998). Antidepressant response in late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry 59 (Suppl 10): 4–8.

Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Decina P, Kerr B, Malitz S (1990). The impact of medication resistance and continuation pharmacotherapy on relapse following response to electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 10: 96–104.

Serretti A, Artioli P, Lorenzi C, Pirovano A, Tubazio V, Zanardi R (2004). The C(-1019)G polymorphism of the 5-HT1A gene promoter and antidepressant response in mood disorders: preliminary findings. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 7: 453–456.

Smith WT, Londborg PD, Glaudin V, Painter JR (2002). Is extended clonazepam cotherapy of fluoxetine effective for outpatients with major depression? J Affect Disord 70: 251–259.

Acknowledgements

Dr Paul Albert provided helpful comments regarding the manuscript. The staff of the Brain Imaging Division and Clinical Evaluation Core of the Conte Center for the Neurobiology of Major Depression, the Kreitchman PET Center, and the Radiopharmaceutical Laboratory gave expert help. This work was supported by US PHS Grants MH40695, MH62185, and NARSAD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parsey, R., Olvet, D., Oquendo, M. et al. Higher 5-HT1A Receptor Binding Potential During a Major Depressive Episode Predicts Poor Treatment Response: Preliminary Data from a Naturalistic Study. Neuropsychopharmacol 31, 1745–1749 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300992

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300992

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Serotonergic receptor gene polymorphism and response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in ethnic Malay patients with first episode of major depressive disorder

The Pharmacogenomics Journal (2021)

-

Epistasis of HTR1A and BDNF risk genes alters cortical 5-HT1A receptor binding: PET results link genotype to molecular phenotype in depression

Translational Psychiatry (2019)

-

Blood-based biomarkers predicting response to antidepressants

Journal of Neural Transmission (2019)

-

Attenuated palmitoylation of serotonin receptor 5-HT1A affects receptor function and contributes to depression-like behaviors

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Serotonin receptors and suicide, major depression, alcohol use disorder and reported early life adversity

Translational Psychiatry (2018)